Sheriff Hutton Castle in the North Riding of Yorkshire

- Michael Smith

- 7 hours ago

- 11 min read

Set on a low ridge with extensive views over the Vale of York and beyond, the imposing ruins of the Neville stronghold at Sheriff Hutton lie at the centre of a fascinating medieval landscape, considerable traces of which can still be seen today.

Sheriff Hutton castle - part of an older landscape

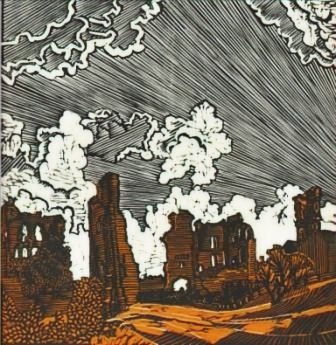

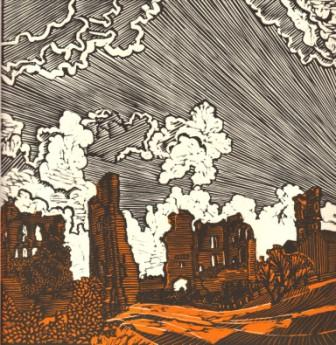

Sheriff Hutton Castle in the North Riding of Yorkshire presents the visitor with surely one of the most dramatic sets of ruins in the whole of the British Isles. Visible for miles across the largely flat Vale of York, what is visible today barely hints at the power and majesty they once represented in the land.

Sheriff Hutton itself boasts two castles. One, the remnants of an earthwork motte and bailey castle, is situated to the east of the village next to the church of St Helen and the Holy Cross.

The other, at the western end of the village, is an enormous quadrangular castle, not dissimilar to those at Middleham and Bolton-in-Wensleydale.

Both the castles, as well as the church and the village also form part of a much bigger landscape; ancient ridge and furrow field systems hint at the life of the peasantry while, to the south, a huge deer park tells of an altogether different way of life.

The earlier motte and bailey castle at Sheriff Hutton

The proximity of the current church and the motte and bailey castle point to a long-standing and intimate relationship between church and aristocracy.

Although architecturally much of the church dates to the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the nave and lower parts of the tower are earlier, dating to the twelfth century, when the castle seems to have been founded.

The motte and bailey is accessible via a gateway in the wall next to the church. The bailey banks are quite substantial, suggesting a strong local power base.

As many authors have highlighted in recent years, timber castles remained in use well into the fourteenth century. Iolo Goch’s poem about the hall at Sycharth castle, former residence to Owain Glyndwr, is not only testament to this but also to the impressive nature of such buildings’ internal decoration and appearance.

At Sheriff Hutton, the size of the earthen banks suggests instead a substantial residence of some importance. The effigy in the church to Sir Edmund de Thwing (or Thweng) of nearby Cornborough (d. 15th October 1344) hints at a continued connection between church, local lords and the earthwork castle well into the fourteenth century.

Notwithstanding, the date of the castle’s founding is unclear. David Cathcart-King, in his monumental Castellarium Anglicanum, considers it to have been a construction of the Anarchy of 1138-1153. The Victoria County History (VCH) states the castle was established by Bertram de Bulmer in 1140.

Others have suggested it may have been established prior to 1100 as the centre of an estate belonging to Aschetil de Bulmer. De Bulmer was Sheriff of Yorkshire from 1115, which may account for the name of the village.

Old aerial photographs taken after the Second World War, and even Google Earth views today, show extensive ridge and furrow fieldworks around this end of the village.

Significantly, they appear to show that the castle was built later than the fields, rather than the village and fields being built around the castle. If it was an imposition on an earlier village site, this may support King’s argument.

Oliver Creighton has suggested that the imposition of the castle represents “the re-orientation of an earlier plan.” Traces of a village bank to the north also hint at a subsequent assertion by way of a planned settlement.

Sheriff Hutton and the Neville family

Certainly, what we see at Sheriff Hutton today is an example of a village which expanded away from the original settlement and beyond its then planned boundaries. The current stone castle tells us why.

In 1382, dramatic events occurred in the village when Sir John Neville of Raby was granted licence to crenelate at Sheriff Hutton, building a huge palatial castle which not only dominated the village but also the local landscape for miles around.

The new castle was designed to “become the heade and capitall of his residence”, according to a reference in the Victoria County History. In other words, this was to be a building of status.

The Nevilles were amongst some of the most powerful figures in the medieval north; the palace built at Sheriff Hutton bears testimony to this. Although it is now much destroyed, a comparison with Middleham or Bolton-in-Wensleydale gives an idea of how it once must have looked.

But unlike these castles, Sheriff Hutton was built to dominate the landscape. What remains of its towers even today stand to nearly 100’ in height, and this is before we consider the impact of its location on its low ridge.

To the south, the power of the Nevilles was further exemplified by a vast deer park, the plan of which can still be traced in the fields and hedges of today.

It is not hard to imagine this sense of power, luxurious living and hunting being at the centre of life, celebrated within the building by hearing stories such as Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, which themselves captured such lifestyles.

The original appearance of the Neville castle at Sheriff Hutton

A hint of Sheriff Hutton’s appearance in the landscape is gained by the copperplate print etched and engraved by the Buck brothers in the early eighteenth century. Despite being relatively crude compared to much of their other work, the print highlights several features now lost.

Not only do we see curtain walls standing to their full (or at least near complete) height, but we are also aware of the many windows and doors which suggest, as at Wressle, a castle deliberately intended as a palace.

The print’s depiction of York in the distance not only places the castle in its local landscape but also hints at its dominance. Here was a castle built as a palatial residence, with views over all the local seats of power; York is small in its shadow.

Although the plain we see in the print is not the deer park, we nonetheless can imagine the park’s flat expanse, further exaggerating the lofty eminence of the Neville palace above it.

A progression towards power - a castle built to impress

In building Sheriff Hutton, the Nevilles employed John Lewyn as their architect, a man responsible also for works at Bolton, Carlisle, Dunstanburgh, Warkworth, and possibly Wressle.

The sheer scale of Lewyn’s resultant palace is astonishing. Originally constructed in three wards arranged in a line, seemingly running from the village green (then the market place), the castle would have treated the visitor to a progression through levels of ever-increasing architectural grandeur towards the inner ward, the extant castle of today.

The Historic England listing describes each of these three wards, or “courts” as follows:

The inner court included the hall, kitchen and the lord's stately lodgings including a chapel. The middle court was described [by a survey and by Leland] as being protected by three great towers, the middle tower forming a gatehouse, but in 1525 this court required extensive repairs to its walls, a section of which over 20m [60’] long had collapsed. The outer court included a brewhouse, horse mills, stables and barns.

John Leland’s words specifically state,

I marked [noticed] in the fore front of the first area of the castle itself three great and high towers, of which the gatehouse was in the middle. In the second area there are 5 or 6 towers.

In attempting to understand this description, if the “three great towers” were not those of the western wall of the inner court, they were in all likelihood arranged across the ridge as the visitor approached from the outer court from the west. These have long since disappeared.

The “5 or 6 towers” suggest the inner court and also imply that they were taller and grander than those immediately confronting Leland.

In other words, the castle proper combined the middle and inner courts, with the inner court being the prime residence in the manner of the Inner Ward at Conwy in North Wales, a castle similarly built on a ridge.

On entering the middle court, visitors would have been aware of the structural massivity of the main palace and the familial power which confronted them. Here, at the entrance to the inner court, was a dramatic gateway above which a row of four painted carved shields, each telling them that this was the house of Neville.

It is notable that while three of these shields bear the arms of Neville only (a red saltire on a silver field), one is different. In the words of the VCH, the panel contains:

"four carved shields, two surrounded by garters and the others by twisted wreaths. The first, second and fourth bear the arms of Nevill and the third Nevill impaling Beaufort [i.e. the heraldic devices divide vertically down the shield to reflect the marriage of Ralph Nevill to Joan Beaufort, daughter of John of Gaunt, in 1396]. As Ralph Nevill, first Earl of Westmorland, did not receive the garter till 1402, the gateway must have been added after that date."

Perhaps this wall and its gateway represent a final phase in the building, cutting off the middle court from the inner court in one last architectural gesture.

Sheriff Hutton, Richard III and the castle's eventual decline

Sheriff Hutton’s demise mirrors the end of the Neville family, in particular Richard Neville – Warwick the Kingmaker. Without male heirs, his death at the battle of Barnet in 1471 led to his estates being broken up.

In the case of Sheriff Hutton, the castle and its estates were forfeited to the crown, and were granted to Richard, Duke of Gloucester (the future Richard III) who became Lord of the North.

Richard III's connections are still celebrated today, with a banner in the church featuring his white boar motif above the fifteenth century effigy of a young man. This figure at one time was thought to represent Richard's son, Edward, who died in 1484; it is now thought to be Ralph Neville, who died nearly fifty years earlier in 1436.

In later years granted to Henry Fitzroy, an illegitimate son of Henry VIII, Sheriff Hutton castle still periodically hosted the Council of the North and remained a palace of some status until the Council moved to York in 1537. Leland described the castle as being incomparable in the north for its ‘princely lodgings’.

It was during this period that the castle gained an impressive, planned garden, the lumps and bumps of which still survive in the ground to the south of the castle. Of note was a roadway with canals on either side, from which the visitor could admire the splendour of the castle on approaching from below.

However, although Sir George Lawson, steward to third Duke of Norfolk, was ordered to put repairs in hand in 1536, the castle continued to decline and in 1548 the castle’s own chapel was dissolved and the castle became a prison.

In 1625, the King’s Commissioners noted,

"The bowels of this worthy pile and defensive house are rent and torn ... the case of a stately castle, the inward materials transposed and the walls ruyned".

This description, whereby only the outer walls (the "case") remained, seems to reflect the view captured by the Buck brothers when they came to etch the ruins in the early 1700s.

By this time, with much of its stonework stripped by the castle’s then owners, the Ingram family, Sheriff Hutton’s days were done and much of its stonework used as building materials.

A hundred years later, when the Victorians were attracted to the site by its dramatic and romantic ruins, demolition had continued to occur at pace; it is recorded that one of the castle’s remaining (curtain?) walls was even pulled down by a team of horses.

Sheriff Hutton castle today

Despite the romantic interest of the ruins in the nineteenth century, little attention was paid to them in the decades following. Attempts were made in the twentieth century to understand the ownership of the ruins and to implement repairs but these came to little.

When I first visited the site as an undergraduate in the early 1980s, travelling from York on my old Velocette motor cycle, the site was very much part of a working farm. The ruins were treated seemingly in the way of all such farm buildings – maintaining some form of functional utility until they fall down through neglect.

Undeterred, I sneaked into the farmyard and then into the castle itself. I was both surprised and thrilled to discover, hidden behind the tractors, ladders, poles and associated rusty farm machinery stacked up against them, the frieze of four Neville shields still asserting their status despite centuries of decay. In all my years of castle hunting, I cannot think of a more precious moment of delight.

Alas, the entrance passageway itself, the gateway into the former palace, was bricked up. Venturing by other means into the inner court, I examined its crumbling features, all the time mindful of an irate farmer suddenly appearing with his shotgun!

Although little remained within the courtyard itself, the northern range contained the extensive remains of cellars and basements. Back then, these were rubble-strewn, overgrown with nettles, and dangerous – but as a young man, such things rarely deter and I was able to venture down into the vaults to engage with them more closely.

In truth, I shouldn't have been there. The whole edifice was in serious danger of complete collapse and there is no doubt my exploration of such fragile ruins was a foolish act. In recent times I have discovered that a report written just a decade after my visit suggested that 90% of the ruins were in need of repointing!

In 2011, however, a significant grant of £900,000 by English Heritage was made for the consolidation of the ruins. Today, although they appear as dramatic as they did to our Victorian ancestors, the ruins of Sheriff Hutton castle are much less vulnerable to time and weather. They are also available to hire as a wedding venue, if you feel so inclined - how times change!

Though now gone the way of all flesh, the power of the Nevilles, once so dominant in the landscape, continues to cast its formidable shadow over the Vale of York today. Sheriff Hutton castle, still standing proudly in its original medieval landscape setting, is a truly special place.

About the author, Michael Smith

I am a British translator and illustrator of medieval literature. I am also an established printmaker, with work in private collections worldwide.

My books, including translations of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, the Alliterative Morte Arthure, and William of Palerne, are published by Wilton Square Books and are available through all the usual outlets. All my books feature my own linocut prints as their illustrations.

To find out more about me, please click here

To buy an original print of Sheriff Hutton castle by me, please click here

Buy my books!

For more details of my translations of medieval romances and how to purchase signed copies, please click here.

Further information about Sheriff Hutton castle

For the Historic England entry for Sheriff Hutton castle click here

For the Historic England entry for Sheriff Hutton church click here

For the relevant entry in the Victoria County History for Yorkshire, click here

For the link to the website for the castle, including a fly-by drone video of the ruins and their village setting, click here

To buy an original linocut print of the ruins of Sheriff Hutton castle by Michael Smith, click here

Comments